Caution: this blog contains references to sexual violence.

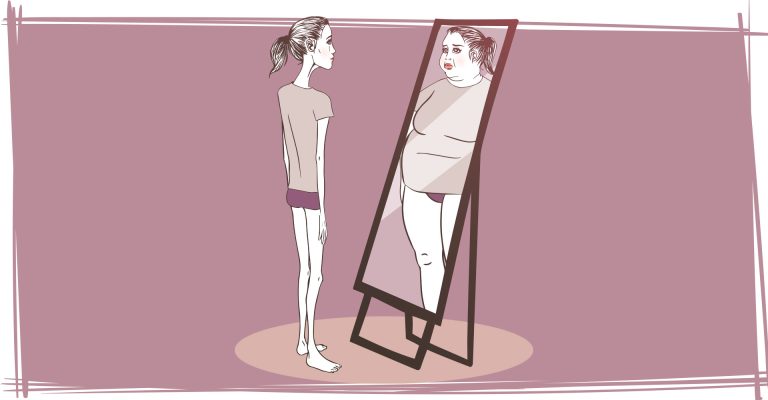

I have always loved clothes: color, textiles, buttons, lace, all of it. For as long as I can remember, I always felt like I had to compensate or justify my existence, by creating and giving objects of beauty. When I think about it, what I most treasure and appreciate about my mom, perhaps the greatest thing she ever did for me, was to teach me to sew at age 9. She wasn’t that good at it, but got me started. And my home economics teacher in 8th grade was a pro and taught me the rest. Sewing became a source of regulation and even pleasure, and I made clothes for everyone. Somewhere I learned to crochet, and even when I was completely disabled and bed-ridden by my nearly fatal anorexia at age 12, I could not do much, but propped up with pillows, crocheted yards of colorful and elaborate lace that I would later use to trim the clothes I would make.

Not surprisingly it piqued my interest to hear the recent interview with high fashion designer Prabal Gurung about his new book, Walk Like a Girl (Penguin Random House 2025.) As it turned out, it was about much more than clothes. Prabal preferred to be called simply by his first name, rather than his full name, as he disliked the patriarchal tradition of carrying the father’s name. And he was hardly fond of his own father, who was deceitful, angry and beat his wife. He vanished and then turned out to be cheating with and later married Prabal’s aunt, his wife’s sister. Prabal, however was devoted and unquestionably securely attached to his beloved mother who remained his ground zero and inspiration throughout his life’s journey.

Born in 1979 in Singapore, Prabal grew up in Kathmandu, Nepal. Before reading his book (which of course I had to, after hearing the compelling interview,) all I knew of Nepal is that it is where people go to climb Mount Everest. I had never imagined life, or a childhood there. The youngest of three, Prabal recounts an early childhood story when he was three or four, and discovered his mother’s red lipstick. Having seen his mother put it on, he proceeded to try it himself. When his mother walked in on him playing with her lipstick, she said, “Oh Prabal no!” She gently took the lipstick from his little fist and said “Here, I will show you how to apply lipstick.” And she lovingly demonstrated how to correctly apply lipstick first to his bottom and then softly, gracefully to his top lip. Similarly, when he loved her, and his older sister’s brightly colored dresses and shoes, she let him play and wear them, which was certainly unique, I was to learn, in 1980’s Nepal.

Gender has been much on my mind lately as I have been studying some of the differences in brain development between genders, in preparation for my talk at the Oxford Trauma Conference. And because there is plenty of disinformation blowing about as if gender and gender non-conformists are a “fad” or a hoax, or some sort of sin. This surprising openness to Prabal’s early delight in what were clearly not the gender norms of his culture piqued my curiosity, and I was further to learn that Prabal’s is also a story of how a secure early attachment is the “base layer.” With that as a foundation, a child is somewhat inoculated against later incident trauma, of which as I would come to find, Prabal would have plenty. On reading the book, I was to find it raised further questions of great interest to me. Besides some of the more insidious variations of homophobia and intergenerational transmission; and pursuit of our dreams, or our apparent dreams, what might be our primary purpose, and even larger questions of identity.

Homophobia

Prabal’s school life was a wide departure from his accepting home life. His hostile father being largely absent, the loving environment with his mother and older brother and sister was accepting and encouraging of his being himself freely. In school he was teased and bullied mercilessly, and shamed for being effeminate, non-athletic, and not particularly scholarly.

In his adolescence, he was sent away to boarding school in Delhi, India, which was hardly better. There he began to have the confusing and infuriating experience of repeatedly being both bullied and raped or gang raped by the very boys who mocked him. Prabal rage and affront simmered and grew as he got older, although he kept the secret of the repeated sexual assaults, he did not attempt to hide his nature. He continued to love beauty: color, texture, fabric and clothes. He admired the traditional and cultural dress of Nepal and India, the deep silken hues of saris and other draped garments worn by his mother and other traditional women, and he took up drawing which gave him comfort in the brutal loneliness of his youth. When he wanted to pursue fashion design, his mother did not dissuade him, and when he was of college age, he departed for New York, USA, a young gay Asian alone in a big world with a big dream.

Meaning

New York was only slightly more accepting, he was to discover. There he encountered racism that garnered the slur “Gaysian,” which is I was to learn, the gay Asian equivalent of the “n” word. Buoyed undoubtedly by the foundation of secure attachment with his beloved mother, whom he never ceased to think of as his anchor and his fountain of hope, he pursued the seemingly impossible American dream of becoming a designer in the high-end fashion world.

My husband always faithfully saves me the thick glossy fashion magazine of the Sunday New York Times. The photography, the clothing, the mysterious and now decidedly androgynous models with their curious and hard to read expressions, and elaborate hair designs, leave him confusedly shaking his head. He used to flip through them and say “I don’t get it…” Now he quietly slides the magazine over to me. I, however have always curiously viewed the pictures with interest, and seeing them as some sort of modern art form, both the designs and the photography. I am fascinated. High fashion, Prabal was to discover, is a complex hybrid between art and business. One has to find a way to navigate both. As a young immigrant with scant resources, in a vicious and competitive world, not to mention the concrete jungle of New York City, USA. With the necessary combination of determination, perspiration and undeniable talent he soldiers on.

I will jump ahead to the good part. After phenomenal ups and downs, Prabal makes it big in that wild and crazy world of high fashion with its unimaginable price tags, designing and making gowns for Oprah (one of his first great inspirations,) Michele Obama, Madonna, Demi Moore…to name a few. Ultimately his is able to start his own label and truly made a big name for himself in a very exclusive world. It is a great story. But it gets better. Prabal begins to ask the larger questions, what matters really? What does it all mean? He realizes he wants to advance the culture and well-being of his own people, and to promote and support the traditions and well-being of people from the Developing World.

Such important self-inquiry, what really matters to me? Fame and fortune, and the competition that surround them are tantalizing, and ubiquitous, and too many can get lost in the weeds there, including us if we are not mindful. Interestingly, and frankly to my surprise, Prabal found his way into therapy, again unique for his culture and in that high profile world, at least as far as we know. So, all that being said, enjoy your pretty clothes! I love my Prada pants (that I paid almost nothing for!)

Today’s song (Although this song is a different race, and story, it captures the same essential and unifying theme):